As Easter passes, I reflect upon the concept of rebirth, as fantastic as it may seem, but today of all days it seems possible.

Is organ transplantation rebirth, a do-over, or is it simply the continuation of many years of battling chronic kidney disease with a degree of improvement?

The moment of the transplant, when the kidney starts working inside the body of the recipient, is nothing less than a miracle, only comparable to birth in medical terms. Based on my experience with three transplants, that euphoria continues for a time period after the procedure where gratitude and happiness are dominant while fear for the future is suppressed.

The recipient and the donor recover together in many cases, as it was in two of mine (father and sister) and create a bond stronger than they had before. That bond of course also includes complex feelings of fear for the donor’s future health, and fear of messing up the gifted kidney.

Over time, the new kidney settles in, and much of what the recipient could not do before is possible. In my case, I was able to work full time, travel, do sports, eat and drink freely and be happy since I was not so tired or in pain anymore.

However, over the long term, due to the lack of new and better immune suppressants to preserve the organ safely, the side effects and the complications become more serious and impact life in a major way. Headaches, tremors, hypertension, diabetes, gastrointestinal issues, infections, cancers, mental health problems such as anxiety and depression, as well as the decline of kidney function lead back to the situation prior to the transplant.

I have no illusions of living forever and even less of living without pain or suffering. It is part of life’s cycle to start healthy and new, and end old and broken.

All I am seeking is a little longer to enjoy the freedom and happiness. I savor the time before I have to go back to that broken state from where I was saved – not just once but twice.

Thank you Pappa and Lisa. And thank you to the family who decided to donate their daughter’s pancreas to me.

By Jeanmarie Ferguson

Without our medications, we cannot have a successful transplant journey. According to CVS Specialty Pharmacy, up to 20 percent of Kidney recipients are non-adherent to immunosuppressants. Once we have a transplant, anti-rejection medications are our new besties. We leave the hospital with so many new medications. How in the world can we possibly keep all of them organized? It can seem so overwhelming.

I put together a few tips that will help you get and stay organized. Transplant centers generally give you a game plan when you leave the hospital. My transplant center even set up all my prescriptions with a specialty pharmacy after surgery. Although all that worked out really well in the beginning, and initially it is all you think about. But as you start to heal from the surgery and feel better with more energy, life really begins. You begin living a fantastic life. After all, that is the whole point of receiving a transplant. Work, family, and friends take over your life. Your quality of life is now the best it’s been in years. You are consumed with going out to restaurants, seeing friends, going on trips, work, and family. The transplant can become a distant memory.

However, your medications cannot take a backseat to your newfound freedom. You cannot ever forget to take your medications. They will forever be the most important thing you can do to ensure your transplant is successful. When I first started out with my transplant in 2006, apps weren’t a thing. With apps, I have found, things can be so much easier to keep track of—especially keeping our medications organized.

I really love the Medisafe app. There are so many others available for free. Apple even has a health app. Sometimes it might seem silly to have an app to remind you to do something that you do every single day at the same time. But there are so many times that I am distracted with doing an activity. So, for me, it is beneficial. The apps are nice in also keeping a nice list of medications and doses. It’s easy to have an updated medication list for your doctor appointments.

Another use of apps that I have found to be extremely useful is the apps for the pharmacy that are available. I have my personal favorite pharmacy where I live. The app allows me to order medications or ask them to submit to the doctor for a refill. It’s convenient to be able to see all my prescriptions in one app. I like to use just one pharmacy for everything because they can keep track of interactions. The pharmacist caught an interaction of medications once that my doctor did not. It’s always good to have checks and balances.

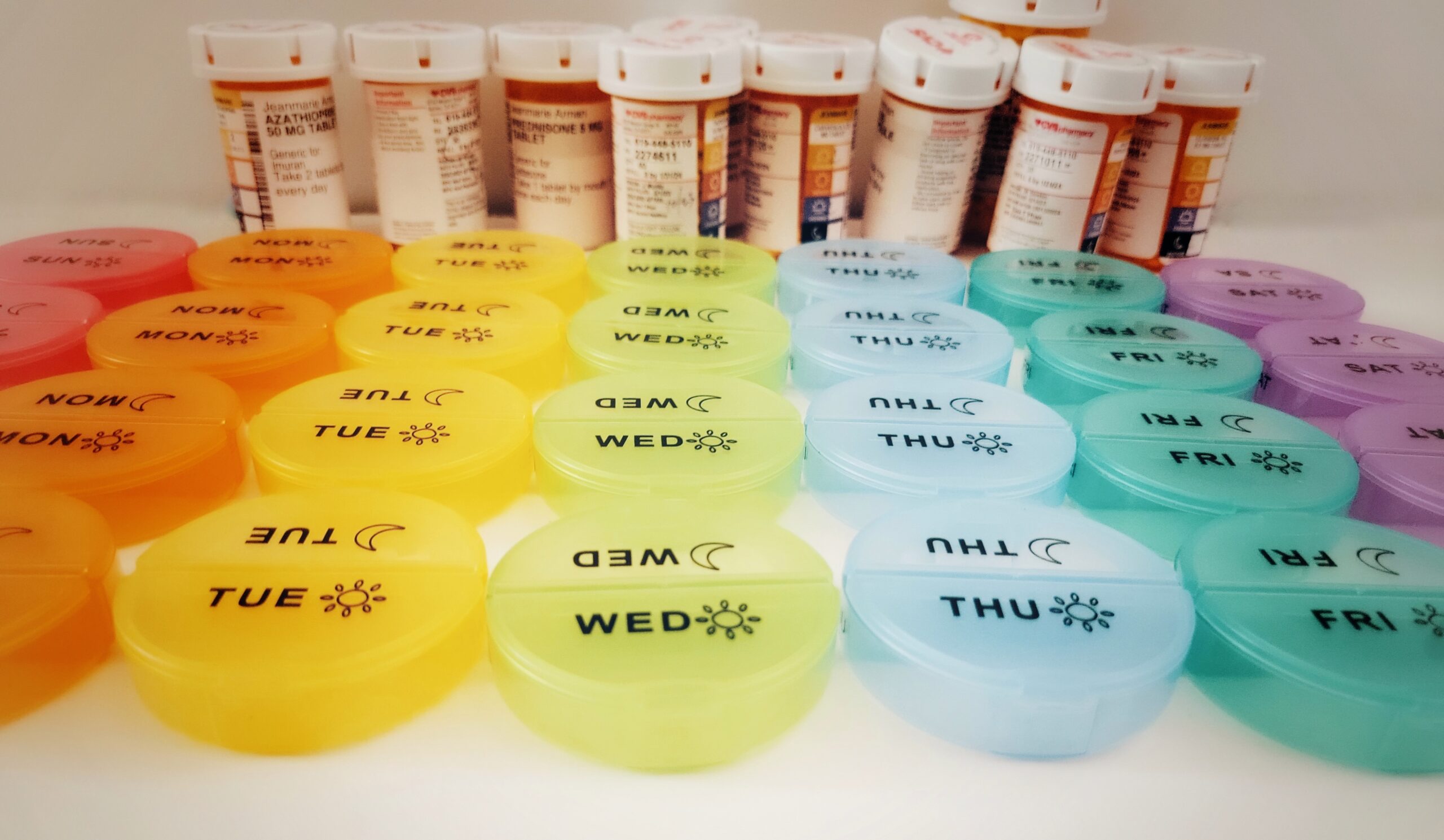

I personally love to use pill organizers. I have tried all sorts of them over the years. Amazon has so many great ones to choose from. You can find one that will fit exactly what will work for your needs the best.

Something I have learned over the years that cannot be stressed enough is if you need help with your medications, ask. Ask your doctor. Ask anyone on the transplant team for help. Ask the Social Worker. Ask your Coordinator. They have lots of resources to be able to help you. We all can go through hard times. We can lose a job and lose our health insurance or we can switch insurance and there is a gap in coverage. Lots of life challenges can hinder getting your medications. Many of the pharmaceutical companies offer copay cards that assist in the payment of the copay. Never be afraid or embarrassed to ask for help. The medications are so important to the success of the transplant and your life.

“Don’t be afraid to lean on others when the weight of the world feels too heavy.” -Unknown

By Jeanmarie Ferguson

One of my favorite things to do is travel. I love experiencing new places and people. I made the mistake of being afraid to travel initially after my transplant in 2006. However, I realized that with a little planning and paying attention to important details, I could and should travel. Traveling sparks a light in me and I feel more alive than ever. After being given a beautiful gift of life, I should get out into the world and explore.

In the last 10 years, I have traveled to different states and cities throughout the United States. There are so many beautiful places here. But now I am ready to embark on my very first international trip. This is by far the most significant goal and dream I have ever had. I have been in love with Italy and Italian art since I was 15 years old. I am so excited and nervous. I have been waiting for years for the right time. I decided there was no better time than now.

I started planning this trip years ago and then the pandemic happened. I postponed my dream once again. I allowed self-doubt to take over my thoughts, feeling that it wasn’t realistic to combine international travel and a transplant. The self-doubt was strong.

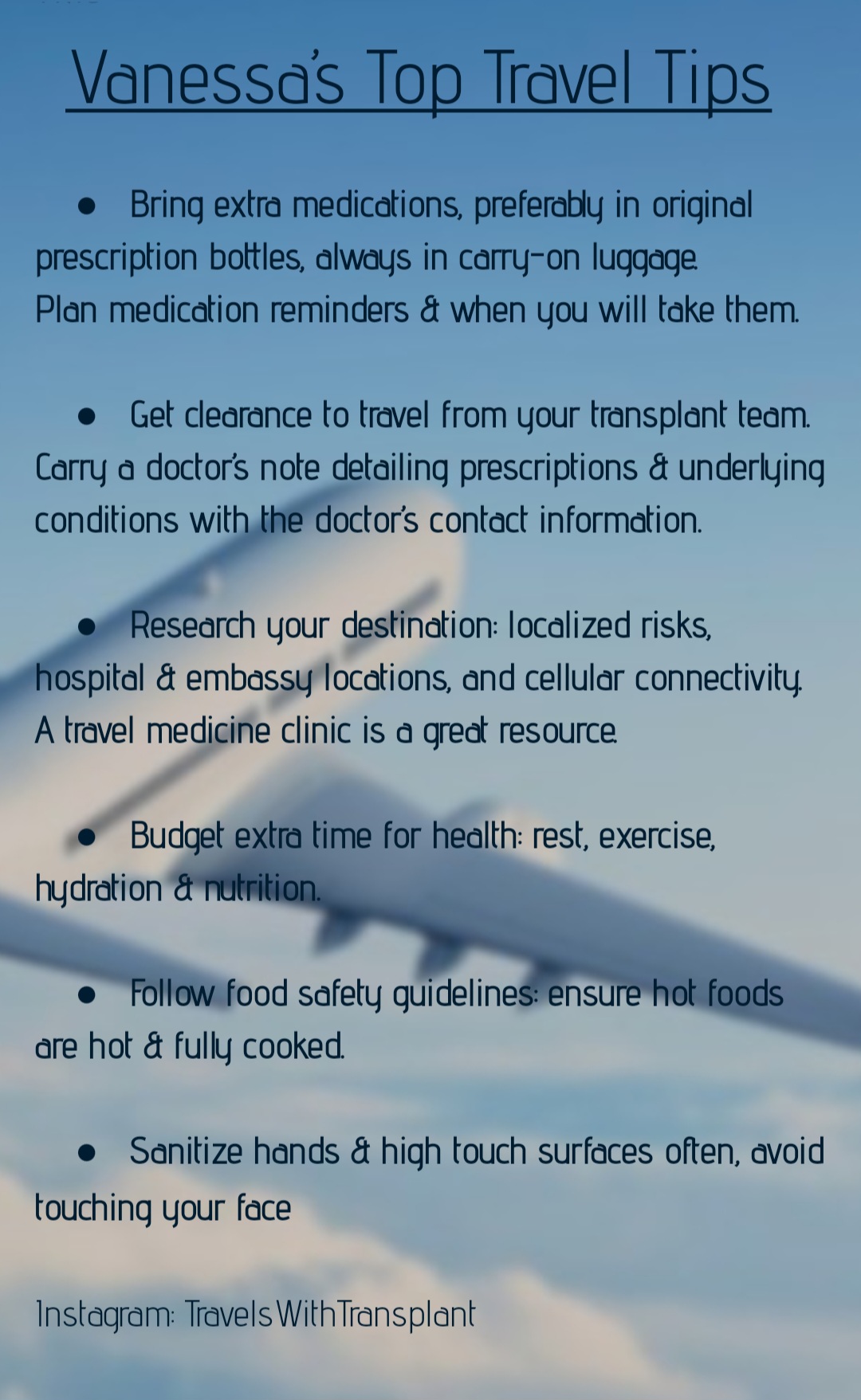

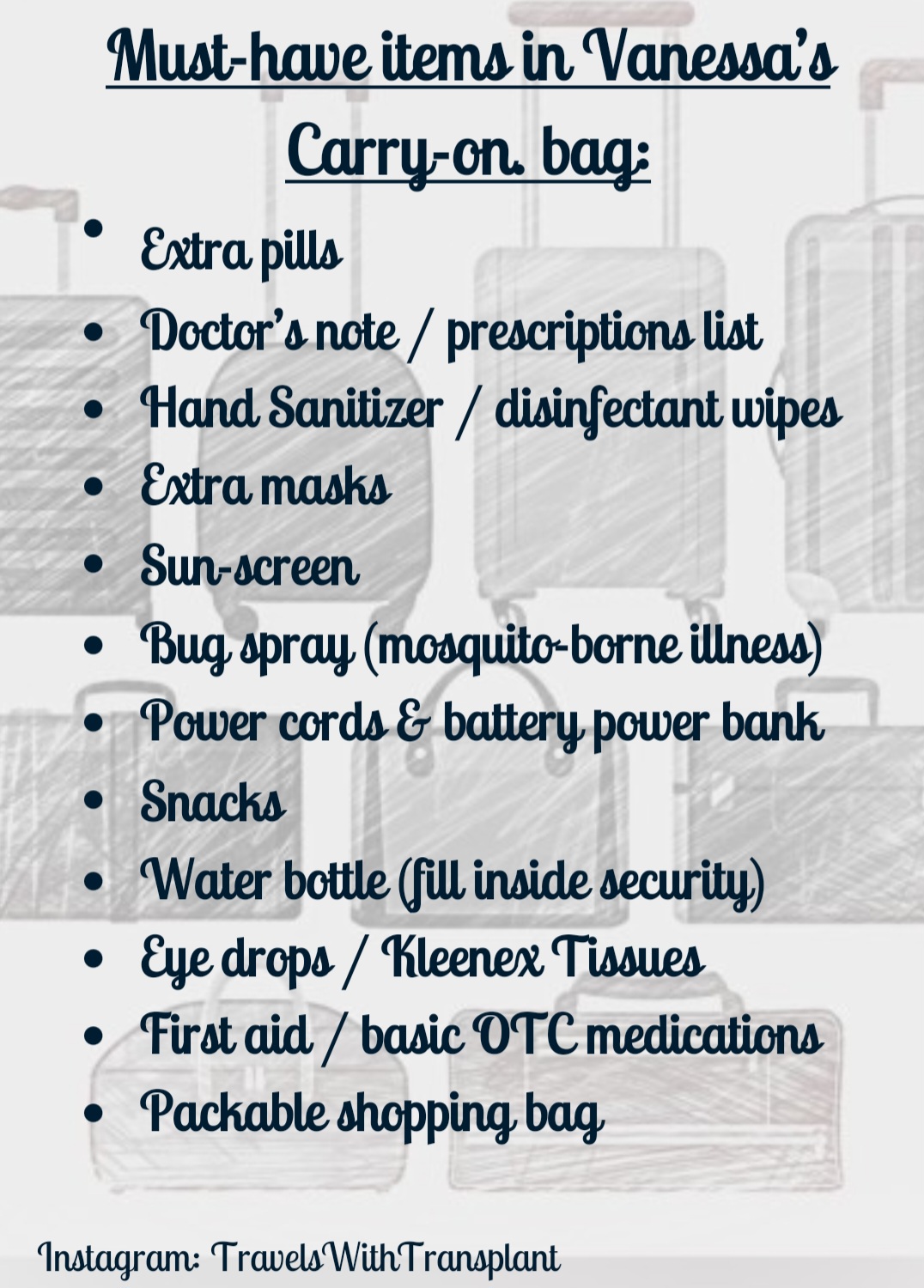

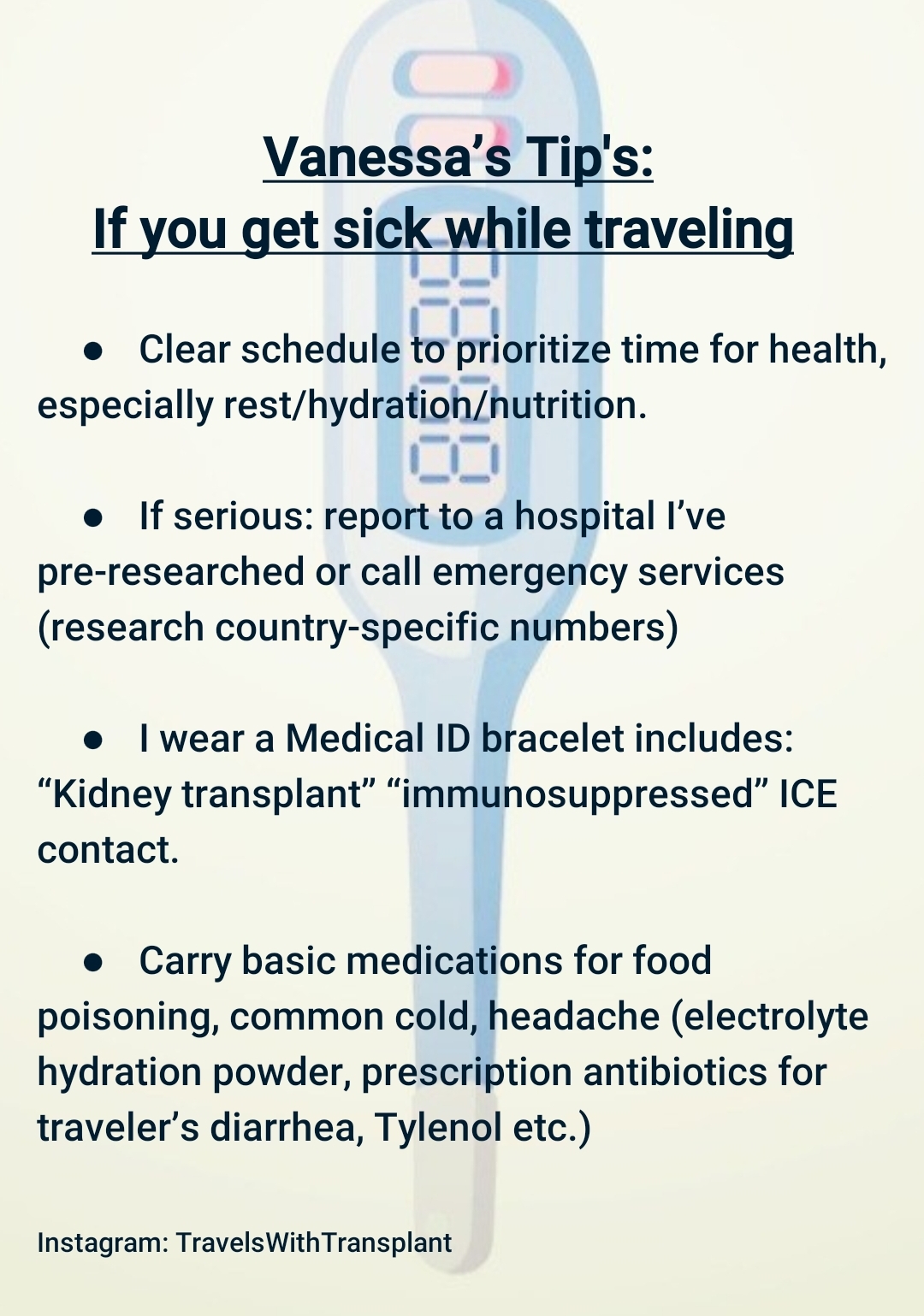

While scrolling through Instagram, I found an account called TravelsWithTransplant. I was so inspired by the tips Vanessa was providing for traveling with a transplant. It gave me a confidence boost to see all the magnificent places she has traveled with a transplant. That is when I decided I was going to make my dream a reality.

I reached out to Vanessa and discussed the trip I was about to take. And I shared my plans to write about it on Transplantlyfe. I had so many questions for her to help ease my thoughts about traveling.

Vanessa is such an amazing transplant recipient with an inspiring story herself.

Vanessa received her kidney transplant over 5 years ago, at age 33, as a result of progressive autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. As a career pilot, she has traveled extensively both pre and post-transplant. She credits a great deal of her success to budgeting extra time for her health, keeping plans flexible, and maintaining a positive attitude. She loves advocating travel solutions to the transplant and chronic illness communities who inspire her daily through their own life and travel journeys.

I asked her to share some of her top tips while traveling. She was so gracious in her response. I learned so many great things to make my trip go so much smoother and remove some of the anxiety about traveling so far from home.

My biggest concern with traveling internationally is knowing when to take my medications once I am in a completely different country. Vanessa recommended using the Medisafe app. I have been using it for a few months now. I like the daily reminders to take my meds. Without our anti-rejection medications, we can’t be successful with our transplant. Of course, talk to your transplant team for advice on how to handle the medications if traveling to a different country or time zone. My team recommends if I take my anti-rejection medications at 9 am and 9 pm Pacific Time, I will take them at 6 pm and 6 am in say Italy. They are 9 hours ahead of us. So the time I would take the anti-rejection pills will be 9 am and 9 pm Pacific time no matter where I am in the world.

Since our medications are the most important item that we take on our travels, they must always go in your carry-on bag. I also take an extra week of medications with me in case of any delays with getting back home.

Another important tip is that we must drink plenty of water. I noticed through some of my travels, that travelers don’t realize you can take an empty water bottle with you through TSA. Almost every airport I have been in has an area where you can fill your water bottle for free. I usually do it right away and one more time before I board the plane.

When I create my itinerary, I always allow for rest days. Sometimes after being on an airplane for a long period of time, with a time zone change, my body gets a bit upset. That is why I schedule those days to just rest at the hotel or wherever my accommodations are. It gives me a chance to enjoy the days that I have something awesome planned. And if I happen to feel just fine on a scheduled rest day, I will get out and explore. I think it’s important that we are gentle with our bodies. They’ve been through a lot.

I hope these tips have been helpful. And I hope they give you the courage to get out and live your life as you want. With a transplant, we have been given a beautiful gift of freedom from constant wires and hospitals. It is always best to partner with your care teams before going on a trip. The care team is always there to answer any questions that you may have about any travel plans.

Vanessa continues to inspire me with her wonderful travels! I asked her what her favorite places are that she’s traveled. She said: Cinque Terre, Italy, New Zealand (South Island), and Kyoto Japan. How cool are all those destinations? It opens up so many possibilities for us as transplant patients to get out into the world, taking safe precautions, of course.

I have shared many tips throughout this article. If you have any questions for Vanessa as you decide if you might take a vacation soon, feel free to reach out to Vanessa with any questions. Make sure to give her a follow on Instagram @TravelsWithTransplant for more travel tips.

“Jobs fill your pocket, but adventures fill your soul.” – Jamie Lyn Beatty

Hi! It’s Jeanmarie. I received my transplanted kidney from my father in January 2006. I’ve had many ups and downs over the last 17 ½ years with this kidney. I had gained weight from a combination of medications and/or lack of exercise from not feeling my best. Via a transplant, we can go from having dietary and fluid restrictions to “freedom”. We finally feel free post-transplant. At least I did.

I was so excited to have freedom with food again. Then my blood pressure, cholesterol, and weight increased around year four. I decided I needed to take control of the situation.

I had done extensive research and talked to my transplant and care team about going on a plant-based diet. They all agreed it would be very beneficial. About 3 months in, I lost weight, and my blood pressure and cholesterol started coming back down. My kidney also seems happier. So did the rest of my body. I had the energy again to start exercising.

It can sound daunting to change the way you eat. But the benefits are so amazing that it is worth the effort.

Melissa J. Webb, MA wrote in her article on Helio.com, “Nephrology professionals may not routinely recommend plant-based diets to patients with kidney disease due to concerns over patient acceptance and their ability to follow the diet plan, according to survey results. The results, presented virtually at the National Kidney Foundation Spring Clinical Meetings, also highlighted a lack of patient knowledge regarding the benefits of such diets.”

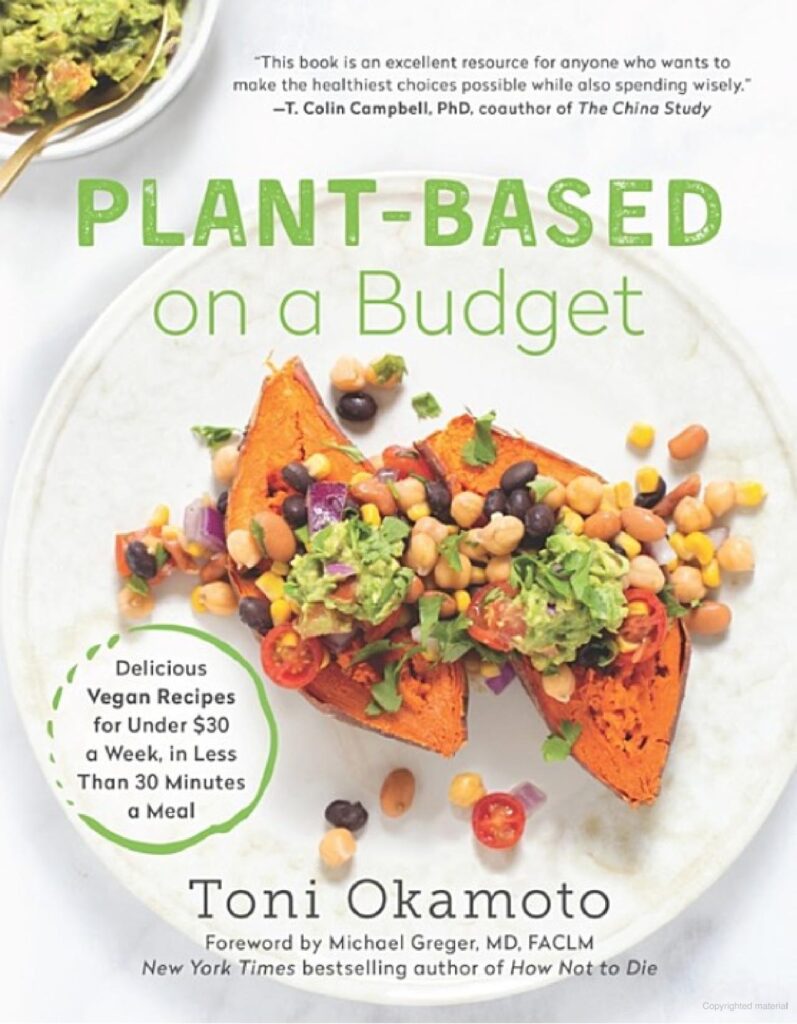

When it comes to starting a plant-based diet, there is so much information on the internet and on social media. Some of it can be so contradictory, making you even more confused on where to start. There is a book that I love called, Plant-Based on a Budget, by Toni Okamoto. (Not sponsored.) It helped me figure out where to begin. There are tips on how to meal plan and prep. It even gives you grocery shopping lists. I love how it taught me how to make balanced meals throughout the week, making sure to not overdo it on protein but get a nice variety of nutrition.

Throughout the years, I have added to the recipes or started to incorporate other recipes I find online so I don’t get bored. I usually pick a day of the week to meal plan and prep for the week. The benefits of meal planning are two-fold. You are less likely to go out to a restaurant or eat fast food and you are not spending tireless hours in the kitchen throughout the week.

I start my morning with black coffee and a smoothie. I like to use Orgain protein. I found that it is the best inexpensive one out there. My morning smoothie recipe is:

You can add or take away anything to the smoothie. In order to not waste any produce, I will prepare and freeze everything. I always have these ingredients frozen and ready to go. This keeps me full until at least lunch. It gives me energy and I don’t find myself wanting to snack.

Some of the challenges I have had with a plant-based diet is eating too much of the processed vegan meats that there are on the market. At the start of the pandemic, I started to notice some stomach issues. I evaluated what I was eating and realized I was eating a lot of frozen vegan meats. At the time, I was trying to minimize the need to leave my house. Once I started eating more cleanly, the stomach issues went away. I feel that with all the transplant medications, we are prone to stomach problems.

I also found over the years that eating strictly too many raw vegetables, my stomach also becomes unhappy. According to an article on the Livestrong website, “Raw vegetables can be difficult to digest due to their high fiber content. However, not fully digesting them doesn’t equal “no benefit.” If raw veggies are a problem for you, cook them first or make sure you’re chewing well enough to take stress off your stomach and intestines.” (Note: making sure the raw veggies are thoroughly washed is especially critical for transplant patients and others on immune suppressive medication.)

The new obsession that I have added to my daily diet is ginger shots. They take away my inflammation. Any joint or muscle aches that I have are also gone. Ginger helps with digestion, reduces cholesterol and lowers blood sugar levels. They make me feel like I am a new woman. I use the recipe on the right but there are so many out there with different variations. You can also add turmeric. Keep in mind only 1 per day. Any more than that can actually cause heartburn.

I have been eating plant-based for 13 years now. My labs usually look very good despite having obvious transplant issues. I still continue to have ups and downs. The medications that we take for transplant can be rough on the body and may cause all sorts of other problems. I’ve been able to keep my body as happy as possible by eating plant-based.

“The beauty of food as medicine is that the choice to heal and promote health can begin as soon as the next meal.”- unknown.

Treat yourself with grace. Every day is different. Some days you can be a superhero and some days you can’t get out of bed. Both are equally beautiful and important.

Dr. Alin Gragossian is a physician with dual certifications in emergency medicine and critical care. She’s also a heart transplant recipient. In what seemed like a split second, everything changed as she went from doctor to patient and changed the course of her career and her life forever.

A volunteer opportunity during high school was the spark Alin needed to ignite her passion for medicine. Born in L.A., she attended medical school in Tennessee before moving to the Philadelphia / New York area for residency. She knew she wanted to work in emergency medicine before beginning her residency, a demanding specialty known for its intensity. Being healthy throughout her life, Alin was up for the challenge. It was here everything began to change.

Towards the end of her emergency medicine residency, one of Alin’s attending physicians noticed unusual symptoms, like taking extended pauses to catch her breath. What Alin thought was just a cold turned out to be anything but, and after one shift, she left the ER only to return hours later, this time as a patient.

Doctors discovered that Alin, a seemingly healthy medical professional in her early thirties, was in acute heart failure. Later on, Alin found that the cause of her heart failure was familial dilated cardiomyopathy, which also affected her father.

She was listed for an emergency heart transplant and transferred from where she worked in Philadelphia to the University of Pennsylvania. Alin describes it as “going from normal, healthy adult to heart transplant patient” in weeks.

Around a week post-transplant, Alin got discharged from the hospital and went home to recover. In June, she returned to finish her residency with a renewed perspective, one that gave her the desire to get involved and raise awareness for the importance of organ donation and transplantation.

3-4 months post-transplant, Alin was able to make a connection with her donor family. Utilizing the local organ procurement agency (OPO), Alin exchanged formal letters with her donor’s mom, Laura. After a year, Alin and Laura decided they wanted to connect directly rather than relying on a third party, such as the hospital or OPO. This communication is how Alin began to learn about Lucy, her donor. Lucy also worked in the medical field. She was a respiratory therapist, loved animals, and had a big family. She was 23 when she died because of a sudden brain cyst rupture.

Recently, Alin had the opportunity to meet Laura and her family, an experience she describes as “a surreal, beautiful and bittersweet experience. A story that transcends life itself.”

Post-transplant patients often wonder where to find a community and who they can talk to. In our conversation, Alin highlights the need for peer-to-peer support. She searched hashtags and found connections with other transplant recipients through social media.

“There are tons of doctors I could talk to, but they are never going to understand what I’m going through,” Alin said. “They understand the science, but they don’t understand the needs of a specific patient. When I leave the hospital, I don’t always have the doctors. I need places to get that support.” She also notes that as a physician, while there are textbooks and medical journals, there needs to be more conversation with patients focusing on lived experience.

When I asked Alin for her thoughts on returning to work and reintegrating into life post-transplant, she shared many of the same concerns as her transplanted peers. Being young and just starting a career, there are many challenges in returning to “normal.” She poignantly described the necessity of processing the old life she was losing before she could integrate into her new life post-transplant. Even if there are many ways to go back to what life was before, the life that exists post-transplant will never be identical. Learning to live one day at a time, Alin says, focusing on the moment and knowing that things take time are what helped her transition to celebrate the life she has now.

Check out Both Sides of the Stethoscope, a podcast hosted by two heart transplant recipients and physicians, Alin by Alin Gragossian and Colby Salerno. You can connect with Alin on Instagram at @a_change_of_heart_blog.

Do you need support? Check out transplantlyfe.com and join our community!

Chloe Temtchine is a singer, songwriter and performer. She is also a double lung transplant recipient. And while the two identities may seem to be conflicting, Chloe has managed to bring them together in a way that exemplifies resilience and grace.

Chloe lived with multiple years of symptoms that no one could definitively diagnose. She tried out different doctors, treatments and hospitals, having all but given up. In 2013, after finishing an album and getting set for a world tour, Chloe suffered an episode that would land her in the emergency room and hand her the devastating diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. She was given labels like “terminal” and “chronic”, and she was told that without a transplant, her odds of survival were grim.

The drugs commonly used to treat pulmonary hypertension, she says, are not allowed in the treatment of pulmonary veno-occlusive disease, and the contraindications made her ineligible for many treatment options that were available. And so she went into research mode. Her options, she says, were to die or find a way to live, and her desire to live kicked in.

Determined to survive, and with the mindset that transplant would be the worst case scenario, Chloe began to put into practice what she calls her 5 key principles to change her life. Those 5 principles were mindset, diet, exercise, quality time with loved ones and creative expression.

Staring small, Chloe remembers when exercise meant walking from the bed to the bathroom. Her guiding principles did work when put into practice, and she did start to get better. Chloe improved in a way that seemed unattainable for someone with her diagnosis. Armed with her oxygen tank, whom she lovingly called Steve Martin, Chloe dove back into making music and living her life.

Until she unexpectedly got worse. While walking on the treadmill one day in her California home, her heart rate shot up to 175. Chloe went into cardiac arrest, and was placed on ECMO while the hunt for a pair of lungs began. There was no time to search for the perfect lungs, and the ones Chloe received were in no way ideal. But on August 5, 2020, she received her transplant.

She says it was like being born, not again, but for the first time. The time on ECMO had taken its toll on her body, and paralyzed vocal chords meant her singing career wasn’t secure. While somebody else may have taken these as signs to shift into a different phase of life, Chloe used them as fuel for the journey.

Her music shifted. “I wrote about superficial things pre-transplant,” she says. “I wrote for myself.” Currently working on a new album, now her music focuses on how far she’s come and the creative energy that fueled her survival.

“Music was my saving grace,” said Chloe. “It’s a form of expression. It inspired me, gave me peace. And everyone has their own version of that. As long as you’re breathing, there’s hope. There’s a way to do it.”

Rather than accept her diagnosis as a reason to never sing again, Chloe says she got creative and strategic in planning how she could still do what she loved, and not let her disease limit her life.

I asked Chloe how artistic expression helped her navigate post transplant life, and what advice she would offer to others. She said “Moments are what matter. This is your life, do what inspires you.”

“It would have been so easy to give up,” she explains, “but you just have to push through it. Keep going. The nightmare will hit you, but on the other side is this heavenly state.”

Pre-transplant, Chloe says she had this terrible idea of what a life with transplant looked like. And she’s glad to say none of that has been her experience.

While a struggle, her life has also been so incredible. With her second chance, Chloe now uses her music as a way to offer hope for others living with pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary veno-occlusive disease and other chronic illnesses.

In sharing her story, she raises awareness for organ donation and transplantation, and started both Brave Kids – a platform for children to turn their struggles into triumph – and the Chloe Temtchine foundation, which focuses on inspiring those living with pulmonary arterial hypertension through entertainment.

For all information on Chloe, links to her various social media accounts and to hear her music, you can go to www.chloetemtchine.com.

Written by Alisha Heibert

Recently I had the opportunity to sit down with Sharron Rousse, a kidney transplant recipient, advocate and the founder of Kindness for Kidneys, to discuss her journey of existing both personally and professionally within the transplant space. She has such a unique perspective, and story, and the kind of personality where, despite never having had a one on one conversation, it felt like we were old friends.

Sharron, who was born and raised in the Washington Metropolitan area outside D.C., was working in education as a school counselor when her first symptoms of kidney disease arose. After a “meet the teacher” night at the school where she worked, Sharron experienced swelling in her legs. It didn’t go away with rest, and she decided that after the following workday, she’d go to the ER. The plan was to work the entire day, but when Sharron arrived and connected with the school nurse, they advised her to clock out early and head to the emergency room immediately. Sharron said the event happened so fast and is a clear memory in her mind; after numerous tests performed at her local ER, a nurse pointed out that her kidneys were failing. Sharron, who had been diagnosed with lupus in 2003, had no indication there was anything wrong with her kidneys, but as more information was relayed to her, she began to wonder about the accuracy of her lupus diagnosis, and whether or not it was her kidney issues in disguise, resulting in the damage having gone unnoticed for so long.

She was transferred from her local hospital to John Hopkins, where she underwent more tests. The most likely option was that Sharron’s kidney disease was linked to lupus, but when she walked out of the hospital a week later with a diagnosis of FSGS (Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis: a rare disease attacking the filtering units of the kidney) the gravity of the situation became more apparent. Sharron was young, with no family history of the disease, having just given birth to her daughter a few months prior. This, she said, was the kind of thing that happened to other people. She was given a steroid cocktail, a combination with damaging side effects to her wellbeing, and did her best to resume a normal life in the face of a devastating diagnosis. It held her numbers at bay for a while, until 2011 when bloodwork revealed her numbers had begun to take a turn for the worse.

For Sharron it felt like a slow decline. She tried every alternative therapy in the book, sought second and third opinions. When it became apparent that dialysis was necessary, and a surgery date was booked to place a peritoneal catheter, she didn’t show up.

Instead she sought another opinion. She saw another doctor who ordered more tests, and one day the phone rang. It was that doctor, asking her how she was doing as her labs had come back and her hemoglobin was critically low. Sharron had reached the point of no return.

She remembers being in that hospital room, praying not only for her life to be spared, but also that she would someday be able to use her experience to help others. “My mindset shifted from focusing on me to helping others,” she said.

At this point peritoneal dialysis was no longer an option, and a perma cath was placed. Sharron began dialysis, and the journey of looking for a kidney donor began.

It was discovered that Sharron’s sister was a perfect match to be her kidney donor, but unfortunately the road was not that simple. The pair went through 5 transplant dates before the transplant was successful. The first date was rescheduled due to Sharron contracting an illness, the second and third because her sister had hemoglobin issues which made the surgical team uncomfortable. Sharron’s sister underwent bone marrow biopsies and saw multiple different doctors, and while Sharron tried to tell her sister that this wasn’t necessary, that she’d find another donor, her sister made it clear that this was her mission.

After months of waiting, the 5th surgery date was a go, and Sharron received her kidney transplant. It was on the 5th anniversary of their successful transplant journey, in December of 2018, that Sharron and her sister started Kindness for Kidneys. While she wasn’t clear exactly or what she wanted this to look like, Sharron wanted to give back to the community that gave her so much. She met with a team, tossed around ideas and applied for grants. They developed the ultimate mission of the organization: to educate, empower, and encourage other transplant patients and kidney warriors in their community and beyond. Sharron saw a need not only for patients to be knowledgeable about what was happening to their bodies, but also for caregivers to be involved. Conversations need to be had among families and in community circles, while at the same time encouraging representation within the transplant community.

“When it’s coming from someone that looks like you, you’re more apt to listen,” said Sharron. The African American community in particular is taught to be strong, to do what you need to do, and the approach Sharron found was one tailored to white presenting individuals. These conversations, she found, not only help those dealing with kidney disease, but also can also help prevent the disease entirely.

Kindness for Kidneys began with donating care packages to dialysis patients during the holidays. Their story quickly caught the attention of a local news crew, and within only a few years they were able to expand their Christmas hampers to multiple different dialysis locations. Just before the COVID-19 pandemic, Kindness for Kidneys started in-person support groups. They quickly had to alter the plan, but this unexpected detour was a blessing in disguise that took their support groups online, and global. The organization is now branching back into in-person support for patients and their caregivers, focusing on thriving with your condition and teaching on topics such as diet and mental health.

I asked Sharron where she wanted to be in 5 years time, and her first focus was on maintaining the vitality of her transplanted kidney. After recently transitioning into being self-employed, she is hopeful for a thriving business as she focuses on education and health consulting. Her ultimate goal for Kindness for Kidneys is to create a one-stop-shop wellness hub for kidney disease patients and their families, both in her local community and beyond.

You can connect with Sharron on Transplantlyfe, where she is an active member of our community. Their website is kindnessforkidneys.org, and they are on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube @kindnessforkidneys.

This is the Lyfebulb CVS kidney care innovation challenge fireside chat. This innovation challenge highlighted the sparking of innovation and care to improve quality of life with people with kidney disease. Significant inequalities exist in kidney care and poor prognosis from the diagnosis point as well as transplant access – the gold standard for care – are common. Patient education for those living with kidney disease remains scant and spotty.

This panel includes Dr. Jesse Roach, a key thought leader representing nephrology at CVS kidney care, Jennifer Miller, an executive in CVS kidney care and a judge of the challenge, the winner, Dalton Shaull, CEO of Omni Life, as well as honorable mention, Sharron Rouse, who developed Kindness for Kidneys, a movement aimed at improving education and equity for kidney warriors.

CVS sponsored this innovation challenge to highlight healthcare inequality in the United States. 35% of people with renal end stage disease are BIPOC. They are 1.3 times more likely to develop kidney disease and 40% less likely to receive a transplant or home dialysis. Some inequalities are due to social determinants of health, like diminished access to technology. Finalists were chosen whose innovations support underserved communities and assist patients find resources and improve their care.

The leaders of each company are personally associated with kidney disease. They are either patients or care partner – for them, the commitment is personal. There were ten wonderful finalists, all of whom represented diverse solutions to address diagnostic, treatment, and support issues. They were asked, how each innovation addresses an unmet need while proving market feasibility and proof of concept.

OmniLife, the challenge winner, is a care provider collaboration tool designed to improve patient care in transplantation and organ failure. It leverages the provider network to increase access to transplant. A clinical decision support tool that analyzes how centers are evaluating patients for transplant is included. This care coordination tool also includes mobile access to track where a patient is at in their journey.

With the monetary award, OmniLife plans to release a patient referral app. Understanding the organ review process is vital to patient transparency in the care continuum, educating patients on how, and by whom, organ offer decisions are made. In transplantation, there is a surgeon-led intake service that reviews the kidney offer. This software would assist how AI and data is leveraged to optimize kidney allocation decisions. Additionally, in the evaluation and listing process, this transparency ensures that patients with the greatest need are at first in line.

The honorable mention winner, Sharron Rouse, is a kidney transplant recipient who publicly shares her transplant experience. During her transplant process she saw a need for greater community connectedness to expand conversation with others. On her fifth kidney anniversary, she founded Kindness for Kidneys, whose goals are providing education, resources, encouragement, and empowerment so patients can actively partner with their healthcare teams.

CVS strives to put the patients’ needs first and meeting the patient where they are. There can be wonderful solutions to patients’ needs but, if those solutions never reach the patients; it’s an exercise in futility. Initial evaluative efforts shone a light on those innovations with the greatest potential to increase connectedness. Within this award process, there were so many connections made within finalists. No one person or organization knows it all; it takes team-based approaches and collaborative thinking to ensure innovation and representation. That is how equitable healthcare becomes possible for everyone.

An Interview with Chet Bennett, our community manager Alisha sat down with Chet to talk about changing the world.

When I interview people for these articles, the focus of conversation is mostly about their lives, and I take the role of a viewer in the retelling of their story. When I spoke with business man Chet Bennett, I was pleasantly surprised when he began asking me about my life. A welcome change and a great introduction to a man who brings this friendly energy to all his relationships!

Chet is the founder and CEO of Bennett Career Institute: a barber and cosmetology school located in the heart of Washington, DC. An alumnus of Morehouse College with a master’s degree from Howard University, Chet has over thirty combined years working in the beauty industry. He started in a tiny salon, a college educated grad, for seven dollars an hour back in 1992 at the encouragement of his pastor, and the rest was history. The Bennett Career Institute opened its doors in 1996, a family business with a desire to educate the next generation (of beauticians, cosmetologists, aestheticians, etc). Being a beauty school that worked primarily with financially disadvantaged individuals, Chet realized one of the barriers to education involved childcare. Thus Bennett Babies was born: a quality childcare facility created to serve students of the Bennett Career Institute that has since evolved into serving the greater Washington metropolitan area.

This story alone is a successful one, but this was only the beginning for Chet. He seemingly had it all: running his own businesses, speaking at engagements, and hosting a radio program. He also had kidney disease that, without a transplant, would ultimately have proven fatal.

Chet describes his diagnosis as shocking, but not surprising. He had high blood pressure, and diabetes. His initially-prescribed diabetes treatment induced gout, ultimately resulting in kidney failure. His doctors warned him this was the path he would go down without a diet change and lifestyle overhaul. An innocuous-enough stomach ache prompted Chet to book an appointment with his primary care doctor, who diagnosed him with kidney failure, and soon he learned he required dialysis to live.

“As a motivational speaker and radio show host, I felt like I failed,” says Chet. He recalled the memory of slinking into dialysis, hiding from anyone who might know who he was, feeling an intense amount of shame around the need for dialysis and a kidney transplant. “I didn’t want people to know Mr. Bennett was vulnerable,” he said.

While waiting for a transplant, Chet had an epiphany. If God gave him the opportunity, if he received a transplant, he would do everything in his power to change the way people look at kidney disease. After a year on dialysis, a donor was found and he received his long awaited kidney transplant, and entered into the next phase of his life.

From this place, the Kidney Kafé was born. What started out as an online talk show turned into a line of seasonings and spices, all with the focus of teaching kidney and dialysis patients how to nourish themselves through food. “So much of our diet is centered on sodium, especially in African American communities,” Chet explained. “And I wanted to show people that flavor can be achieved in other ways.”

With a target audience of 18-30 year olds, Kidney Kafé not only taught people how to cook but provided a jumping-off point for conversations surrounding health and wellness.

His innovation didn’t stop there, and Chet moved into launching the C. Alan Men’s Grooming Salon. The salon is an upscale, modern establishment targeted at men, who are often overlooked in the beauty and self-care industry, not only aspiring to make one look better, but also feel better.

“We want to make the customer feel amazing, special,” Chet said. Kidney disease, dialysis, and body changes can take a huge toll on a person mentally and emotionally, and the need for a safe space where people could come and be taken care of was huge. At the salon you’ll find everything from basic grooming to detoxes curated to what Chet himself needed while undergoing treatment to male units created to combat post-transplant hair loss.

“When you look better, you feel better,” said Chet, “and that’s what we’re trying to do.”

Chet hasn’t slowed down in being an advocate for the kidney disease and transplantation communities, and I asked him if he had a chance to talk to himself prior to his diagnosis, what he would say. He told me, “I should have become more of a health advocate.” Knowledge is power, and when you’re able to identify problems earlier, an entire world of options and treatment opens up. Men, particularly African American men, avoid medical visits for fear of what they might find, and this avoidance can create long term problems.

“If I’m not good for Chet, I’m not good for anyone,” he said. “You have to be mature and responsible enough to take that initiative and take care of yourself.”

Chet Bennett personifies, “Be the change you wish to see in the world.” Even with everything on his plate, this is only the beginning for Chet.

You can find the Kidney Kafé, Kidney Conversations, and everything Chef Benne at kidney-kafe.com

For the shop, speaking engagements, and events, check out calanlifestyle.com

His YouTube channel is Kidney Kafé Chef Benne or you can find him on Instagram @chefbenne_kidneykafe or @chetbeautykingbennett